Home — The Millennium Prize Problems

The Millennium Prize Problems

In order to celebrate mathematics in the new millennium, The Clay Mathematics Institute of Cambridge, Massachusetts (CMI) established seven Prize Problems. The Prizes were conceived to record some of the most difficult problems with which mathematicians were grappling at the turn of the second millennium; to elevate in the consciousness of the general public the fact that in mathematics, the frontier is still open and abounds in important unsolved problems; to emphasize the importance of working towards a solution of the deepest, most difficult problems; and to recognize achievement in mathematics of historical magnitude.

The prizes were announced at a meeting in Paris, held on May 24, 2000 at the Collège de France. Three lectures were presented: Timothy Gowers spoke on The Importance of Mathematics; Michael Atiyah and John Tate spoke on the problems themselves.

The seven Millennium Prize Problems were chosen by the founding Scientific Advisory Board of CMI, which conferred with leading experts worldwide. The focus of the board was on important classic questions that have resisted solution for many years.

Following the decision of the Scientific Advisory Board, the Board of Directors of CMI designated a $7 million prize fund for the solutions to these problems, with $1 million allocated to the solution of each problem.

It is of note that one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems, the Riemann hypothesis, formulated in 1859, also appears in the list of twenty-three problems discussed in the address given in Paris by David Hilbert on August 9, 1900.

The rules for the award of the prize have the endorsement of the CMI Scientific Advisory Board and the approval of the Directors. The members of these boards have the responsibility to preserve the nature, the integrity, and the spirit of this prize.

Unsolved problems

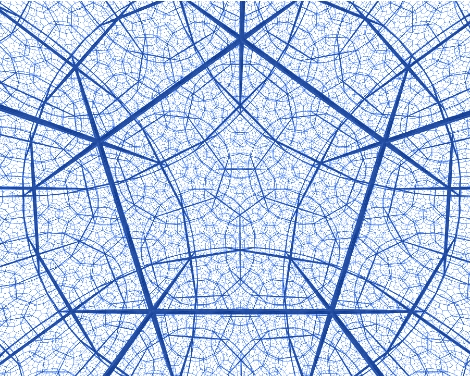

Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture

Supported by much experimental evidence, this conjecture relates the number of points on an elliptic curve mod p to the rank of the group of rational points. Elliptic curves, defined by cubic equations in two variables, are fundamental mathematical objects that arise in many areas: Wiles’ proof of the Fermat Conjecture, factorization of numbers into primes, and cryptography, to name three.

Hodge Conjecture

The answer to this conjecture determines how much of the topology of the solution set of a system of algebraic equations can be defined in terms of further algebraic equations. The Hodge conjecture is known in certain special cases, e.g., when the solution set has dimension less than four. But in dimension four it is unknown.

Navier-Stokes Equation

This is the equation which governs the flow of fluids such as water and air. However, there is no proof for the most basic questions one can ask: do solutions exist, and are they unique? Why ask for a proof? Because a proof gives not only certitude, but also understanding.

P vs NP

If it is easy to check that a solution to a problem is correct, is it also easy to solve the problem? This is the essence of the P vs NP question. Typical of the NP problems is that of the Hamiltonian Path Problem: given N cities to visit, how can one do this without visiting a city twice? If you give me a solution, I can easily check that it is correct. But I cannot so easily find a solution.

Riemann Hypothesis

The prime number theorem determines the average distribution of the primes. The Riemann hypothesis tells us about the deviation from the average. Formulated in Riemann’s 1859 paper, it asserts that all the ‘non-obvious’ zeros of the zeta function are complex numbers with real part 1/2.

Yang-Mills & The Mass Gap

Experiment and computer simulations suggest the existence of a “mass gap” in the solution to the quantum versions of the Yang-Mills equations. But no proof of this property is known.