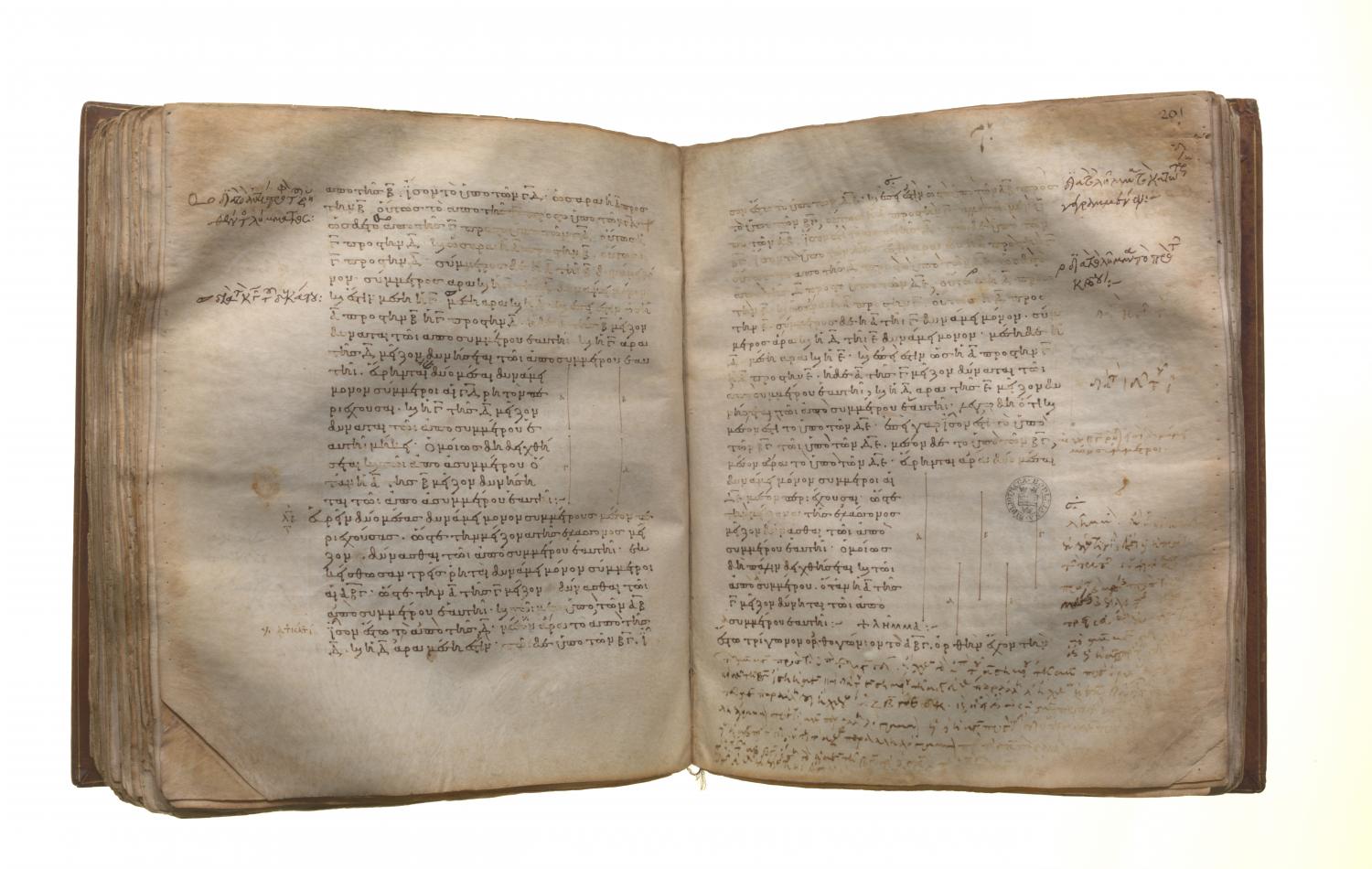

Classification of incommensurables: Book 10 Proposition 32

Translations

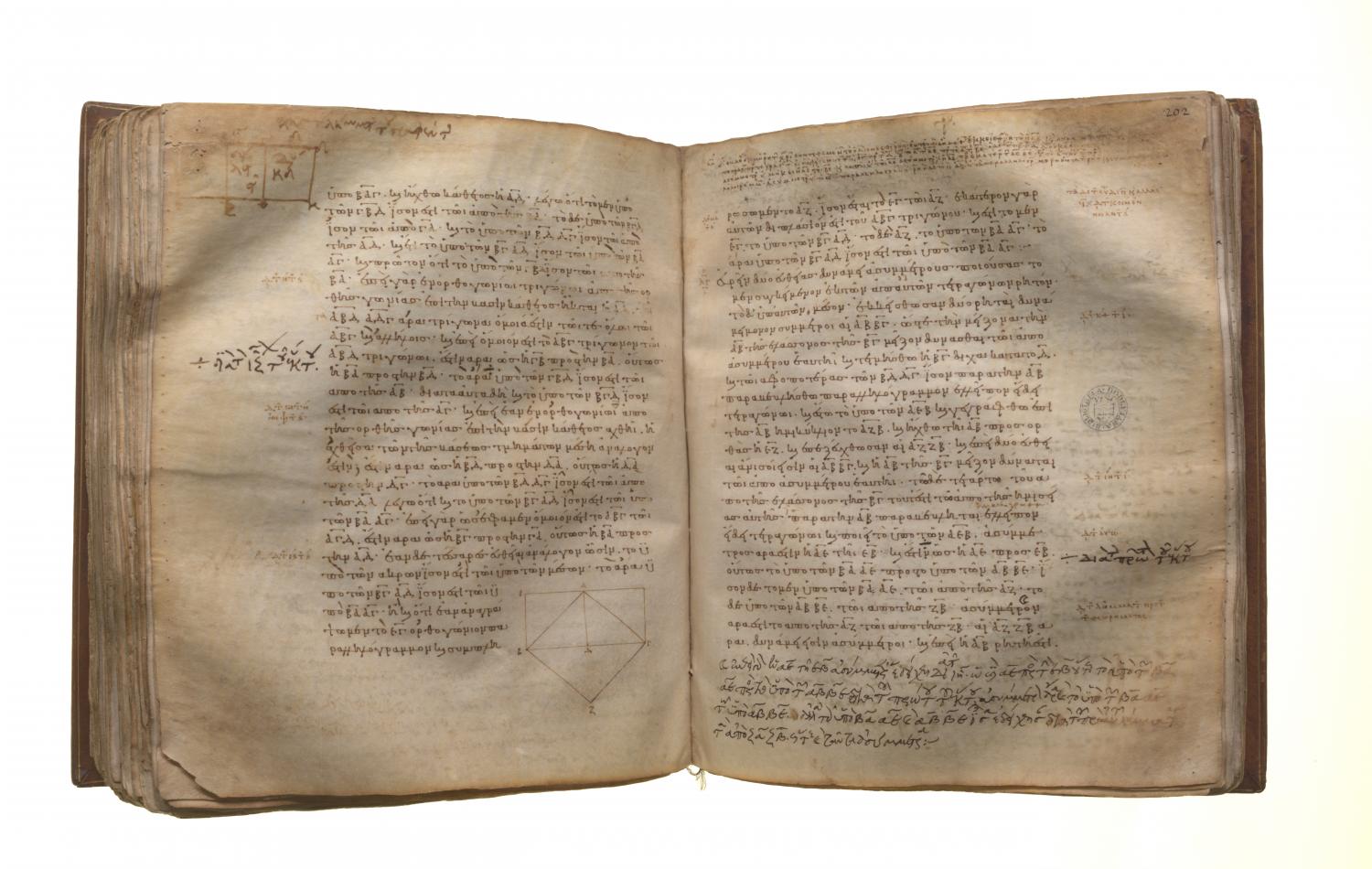

To find two medial straight lines commensurable in square only, containing a medial rectangle, and such that the square on the greater is greater than the square on the less by the square on a straight line commensurable with the greater. Let there be set out three rational straight lines A, B, C commensurable in square only, and such that the square on A is greater than the square on C by the square on a straight line commensurable with A, [X. 29] and let the square on D be equal to the rectangle A, B. Therefore the square on D is medial; therefore D is also medial. [X. 21] Let the rectangle D, E be equal to the rectangle B, C. Then since, as the rectangle A, B is to the rectangle B, C, so is A to C; while the square on D is equal to the rectangle A, B, and the rectangle D, E is equal to the rectangle B, C, therefore, as A is to C, so is the square on D to the rectangle D, E. But, as the square on D is to the rectangle D, E, so is D to E; therefore also, as A is to C, so is D to E. But A is commensurable with C in square only; therefore D is also commensurable with E in square only. [X. 11] But D is medial; therefore E is also medial. [X. 23, addition] And, since, as A is to C, so is D to E, while the square on A is greater than the square on C by the square on a straight line commensurable with A, therefore also the square on D will be greater than the square on E by the square on a straight line commensurable with D.[X. 14] I say next that the rectangle D, E is also medial. For, since the rectangle B, C is equal to the rectangle D, E, while the rectangle B, C is medial, [X. 21] therefore the rectangle D, E is also medial. Therefore two medial straight lines D, E, commensurable in square only, and containing a medial rectangle, have been found such that the square on the greater is greater than the square on the less by the square on a straight line commensurable with the greater. Similarly again it can be proved that the square on D is greater than the square on E by the square on a straight line incommensurable with D, when the square on A is greater than the square on C by the square on a straight line incommensurable with A. [X. 30]Lemma. Let ABC be a right-angled triangle having the angle A right, and let the perpendicular AD be drawn; I say that the rectangle CB, BD is equal to the square on BA, the rectangle BC, CD equal to the square on CA, the rectangle BD, DC equal to the square on AD, and, further, the rectangle BC, AD equal to the rectangle BA, AC. And first that the rectangle CB, BD is equal to the square on BA. For, since in a right-angled triangle AD has been drawn from the right angle perpendicular to the base, therefore the triangles ABD, ADC are similar both to the whole ABC and to one another. [VI. 8] And since the triangle ABC is similar to the triangle ABD, therefore, as CB is to BA, so is BA to BD; [VI. 4] therefore the rectangle CB, BD is equal to the square on AB. [VI. 17] For the same reason the rectangle BC, CD is also equal to the square on AC. And since, if in a right-angled triangle a perpendicular be drawn from the right angle to the base, the perpendicular so drawn is a mean proportional between the segments of the base, [VI. 8, Por.] therefore, as BD is to DA, so is AD to DC; therefore the rectangle BD, DC is equal to the square on AD. [VI. 17] I say that the rectangle BC, AD is also equal to the rectangle BA, AC. For since, as we said, ABC is similar to ABD, therefore, as BC is to CA, so is BA to AD. [VI. 4]