Classification of incommensurables: Book 10 Proposition 60

Translations

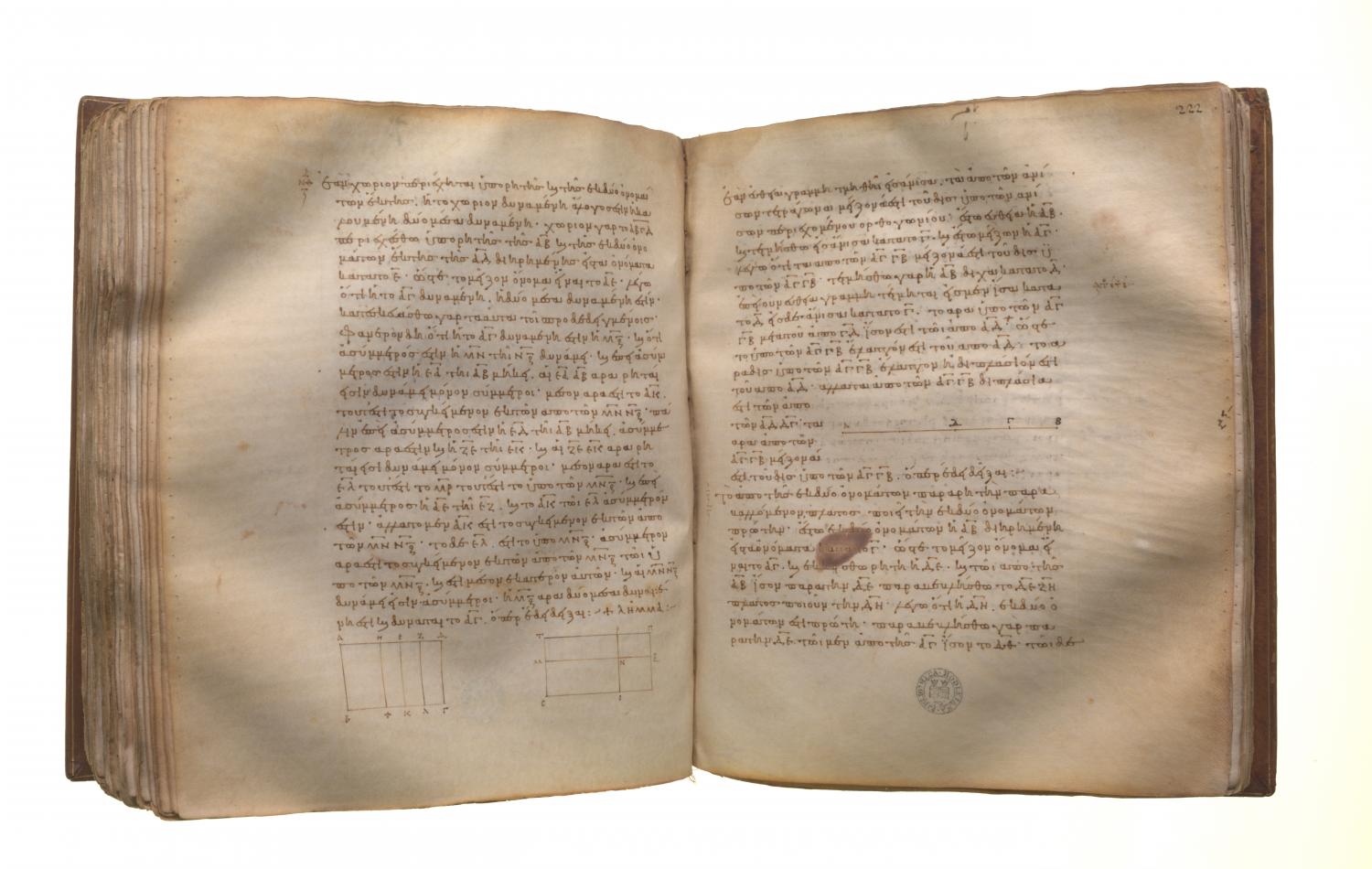

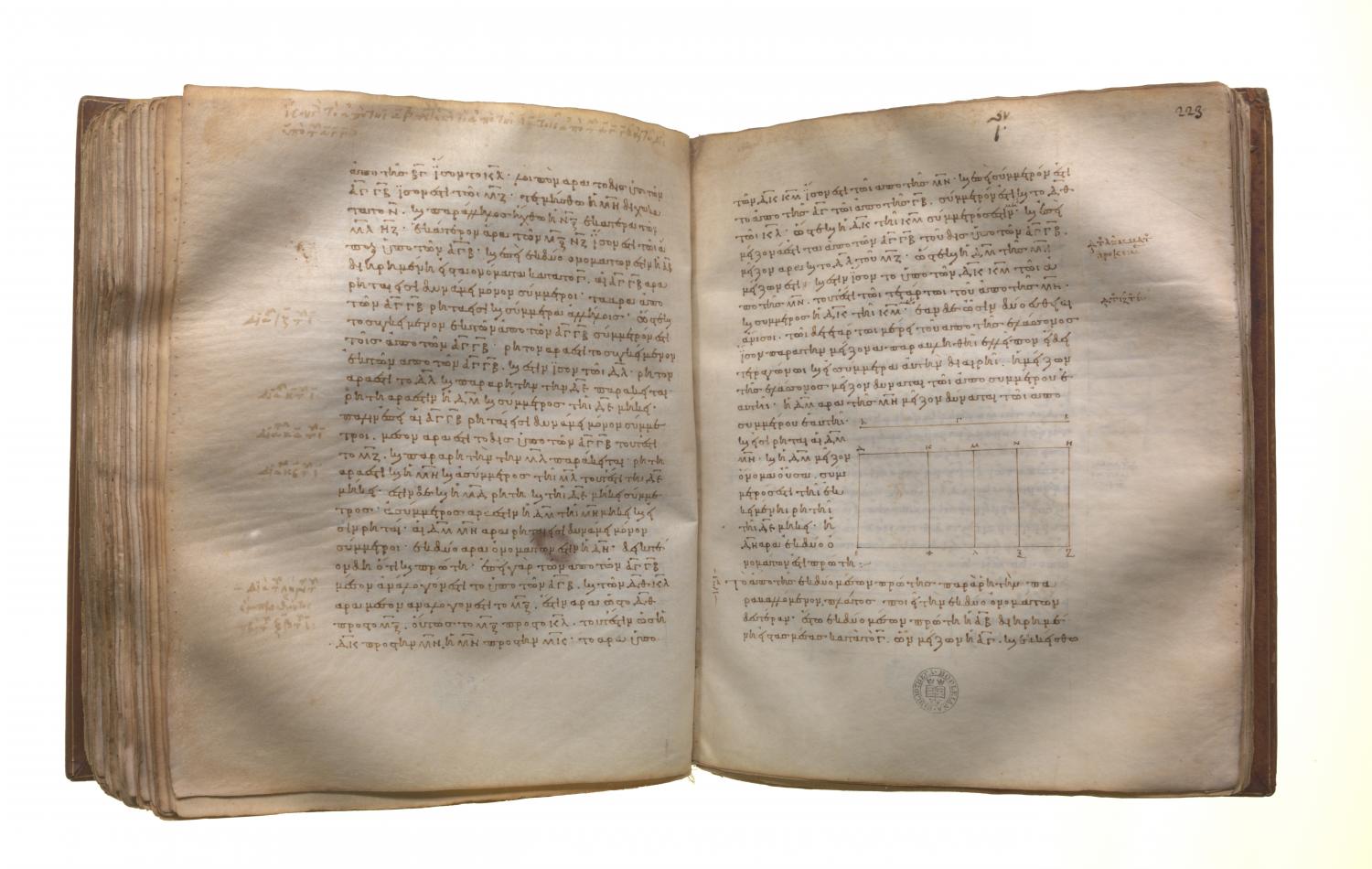

The square on the binomial straight line applied to a rational straight line produces as breadth the first binomial. Let AB be a binomial straight line divided into its terms at C, so that AC is the greater term; let a rational straight line DE be set out, and let DEFG equal to the square on AB be applied to DE producing DG as its breadth; I say that DG is a first binomial straight line. For let there be applied to DE the rectangle DH equal to the square on AC, and KL equal to the square on BC; therefore the remainder, twice the rectangle AC, CB, is equal to MF. Let MG be bisected at N, and let NO be drawn parallel [to ML or GF]. Therefore each of the rectangles MO, NF is equal to once the rectangle AC, CB. Now, since AB is a binomial divided into its terms at C, therefore AC, CB are rational straight lines commensurable in square only; [X. 36] therefore the squares on AC, CB are rational and commensurable with one another, so that the sum of the squares on AC, CB is also rational. [X. 15] And it is equal to DL; therefore DL is rational. And it is applied to the rational straight line DE; therefore DM is rational and commensurable in length with DE. [X. 20] Again, since AC, CB are rational straight lines commensurable in square only, therefore twice the rectangle AC, CB, that is MF, is medial. [X. 21] And it is applied to the rational straight line ML; therefore MG is also rational and incommensurable in length with ML, that is, DE. [X. 22] But MD is also rational and is commensurable in length with DE; therefore DM is incommensurable in length with MG. [X. 13] And they are rational; therefore DM, MG are rational straight lines commensurable in square only; therefore DG is binomial. [X. 36] It is next to be proved that it is also a first binomial straight line. Since the rectangle AC, CB is a mean proportional between the squares on AC, CB, [cf. Lemma after X. 53] therefore MO is also a mean proportional between DH, KL. Therefore, as DH is to MO, so is MO to KL, that is, as DK is to MN, so is MN to MK; [VI. 1] therefore the rectangle DK, KM is equal to the square on MN. [VI. 17] And, since the square on AC is commensurable with the square on CB, DH is also commensurable with KL, so that DK is also commensurable with KM. [VI. 1, X. 11] And, since the squares on AC, CB are greater than twice the rectangle AC, CB, [Lemma] therefore DL is also greater than MF, so that DM is also greater than MG. [VI. 1] And the rectangle DK, KM is equal to the square on MN, that is, to the fourth part of the square on MG, and DK is commensurable with KM. But, if there be two unequal straight lines, and to the greater there be applied a parallelogram equal to the fourth part of the square on the less and deficient by a square figure, and if it divide it into commensurable parts, the square on the greater is greater than the square on the less by the square on a straight line commensurable with the greater; [X. 17] therefore the square on DM is greater than the square on MG by the square on a straight line commensurable with DM. And DM, MG are rational, and DM, which is the greater term, is commensurable in length with the rational straight line DE set out.