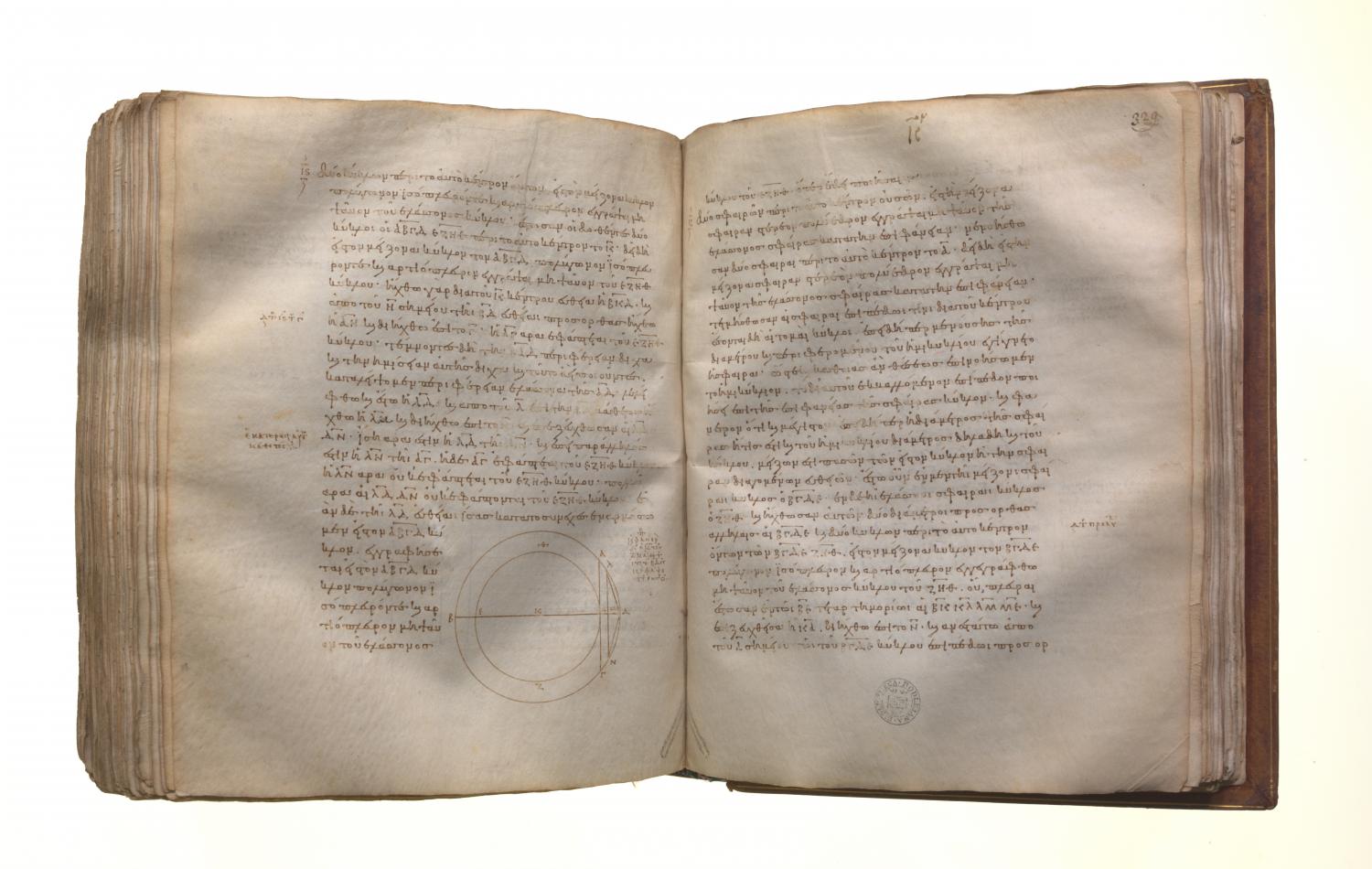

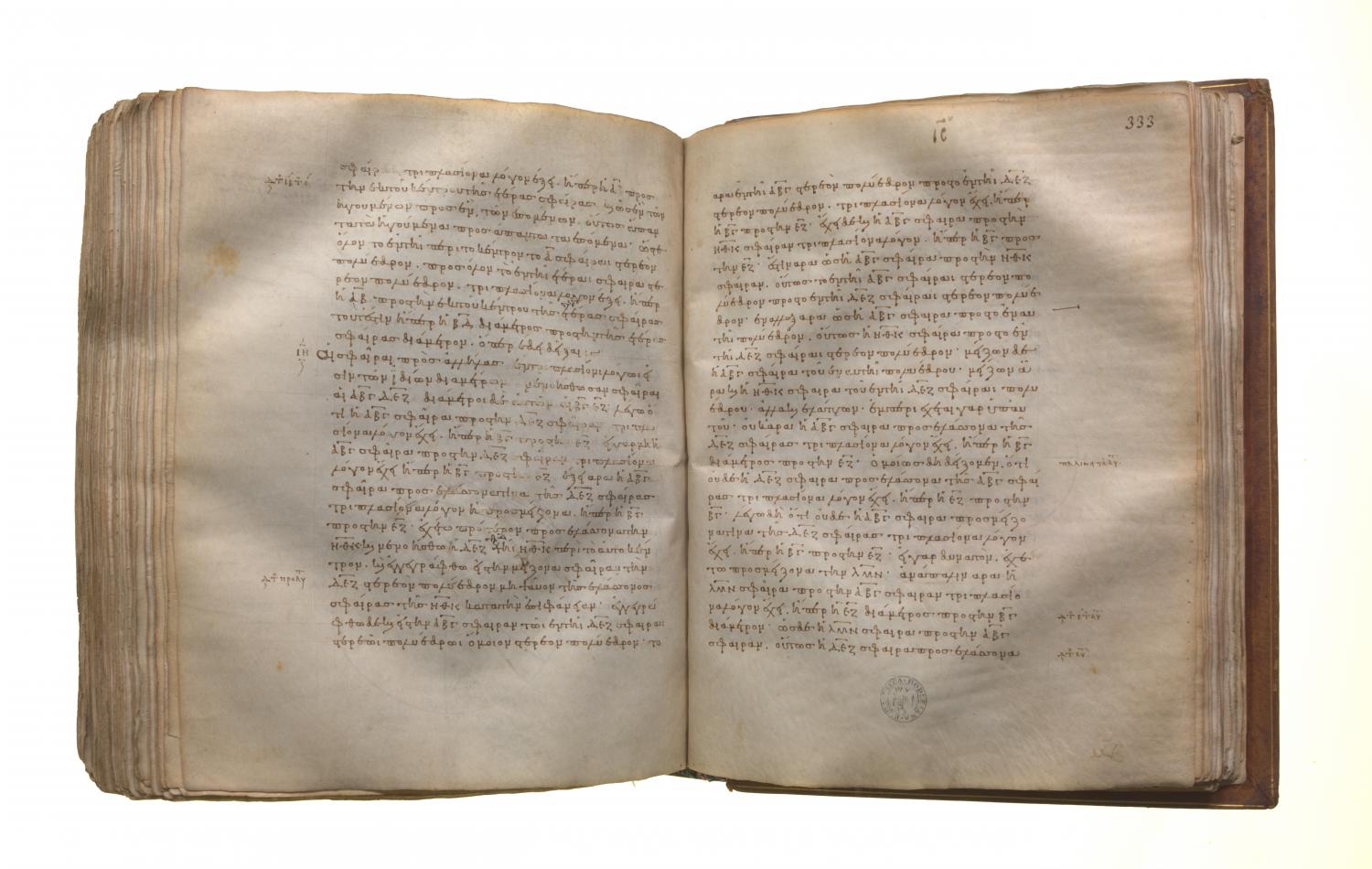

Measurement of figures: Book 12 Proposition 17

Translations

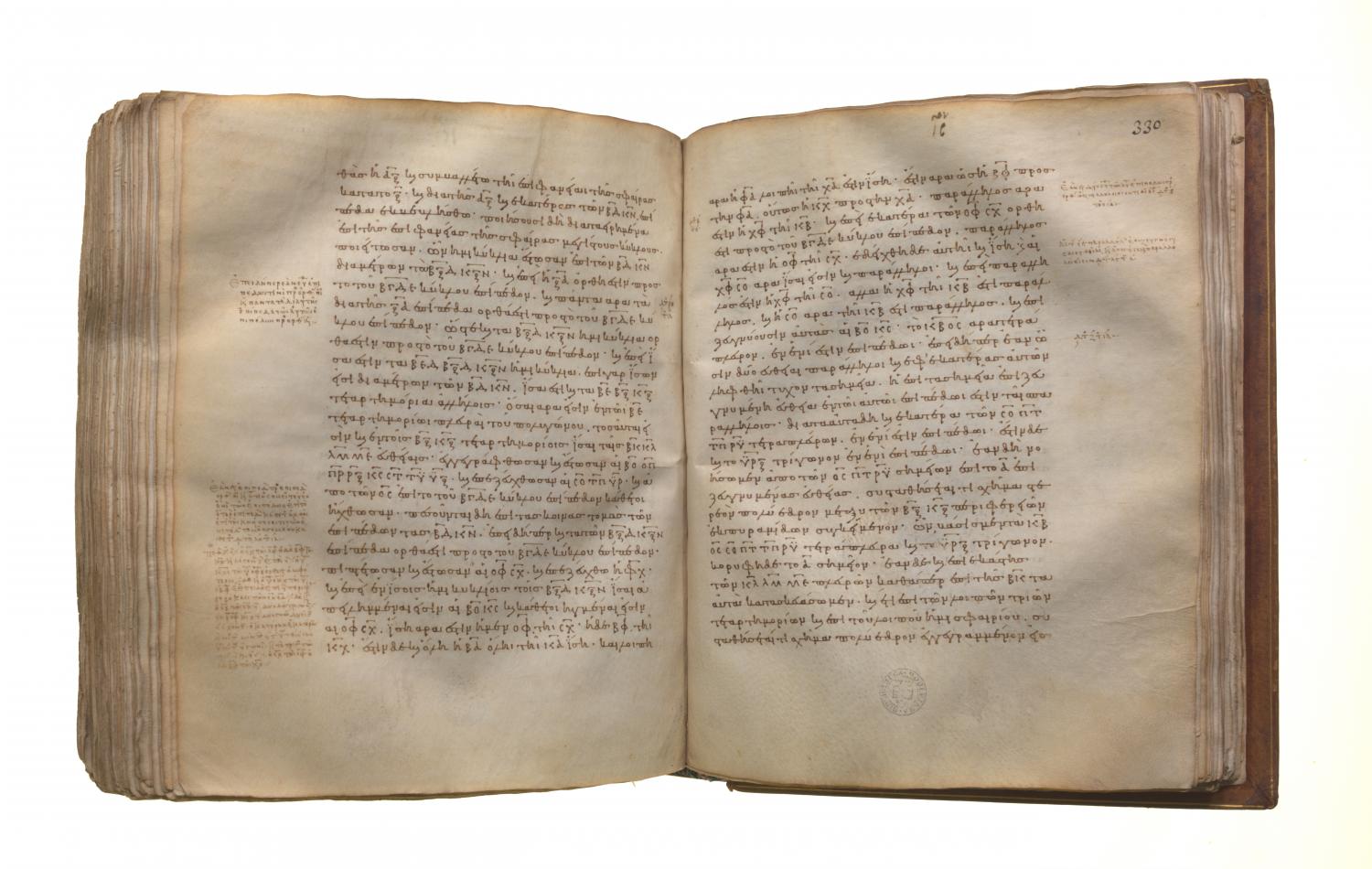

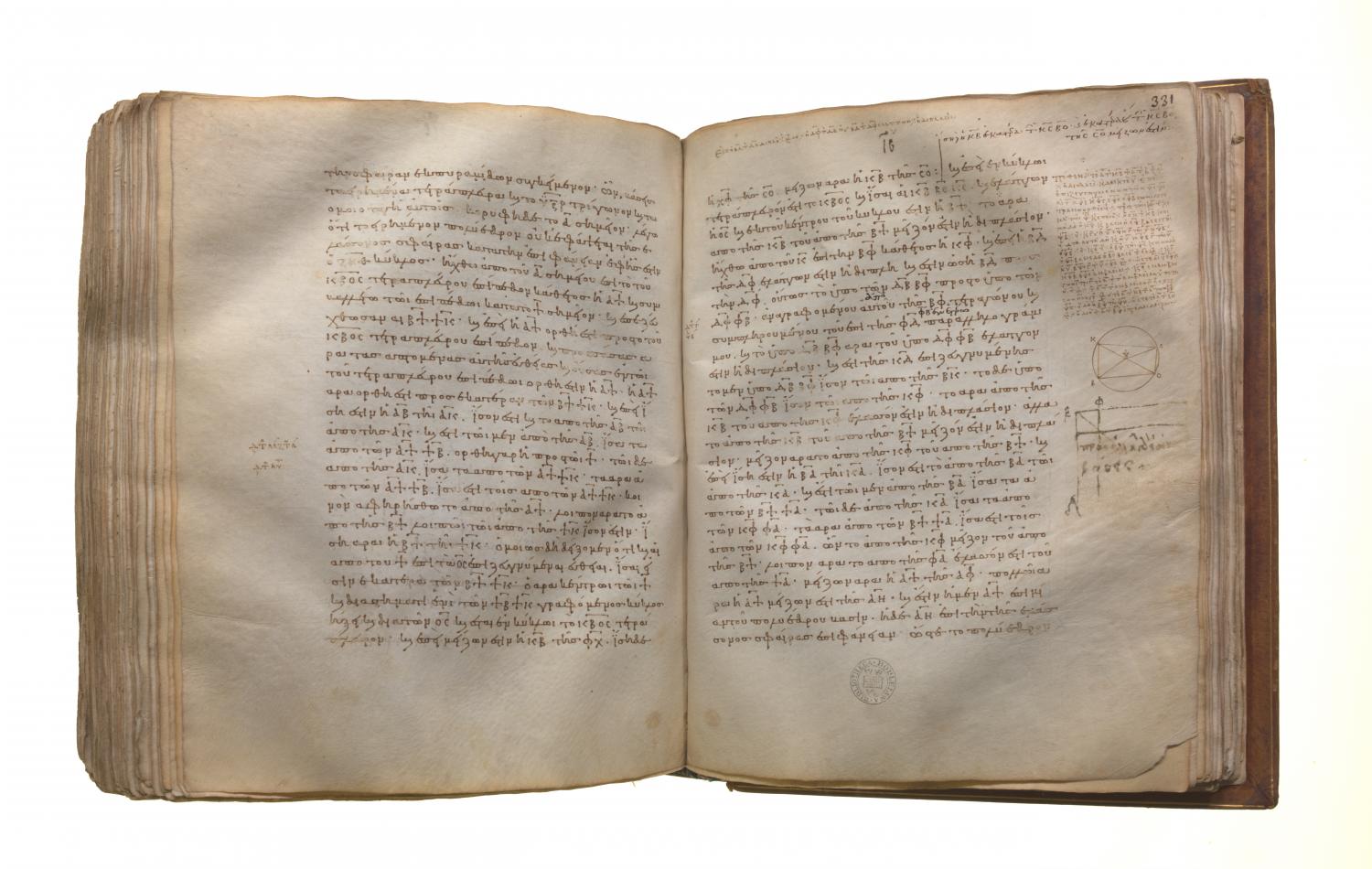

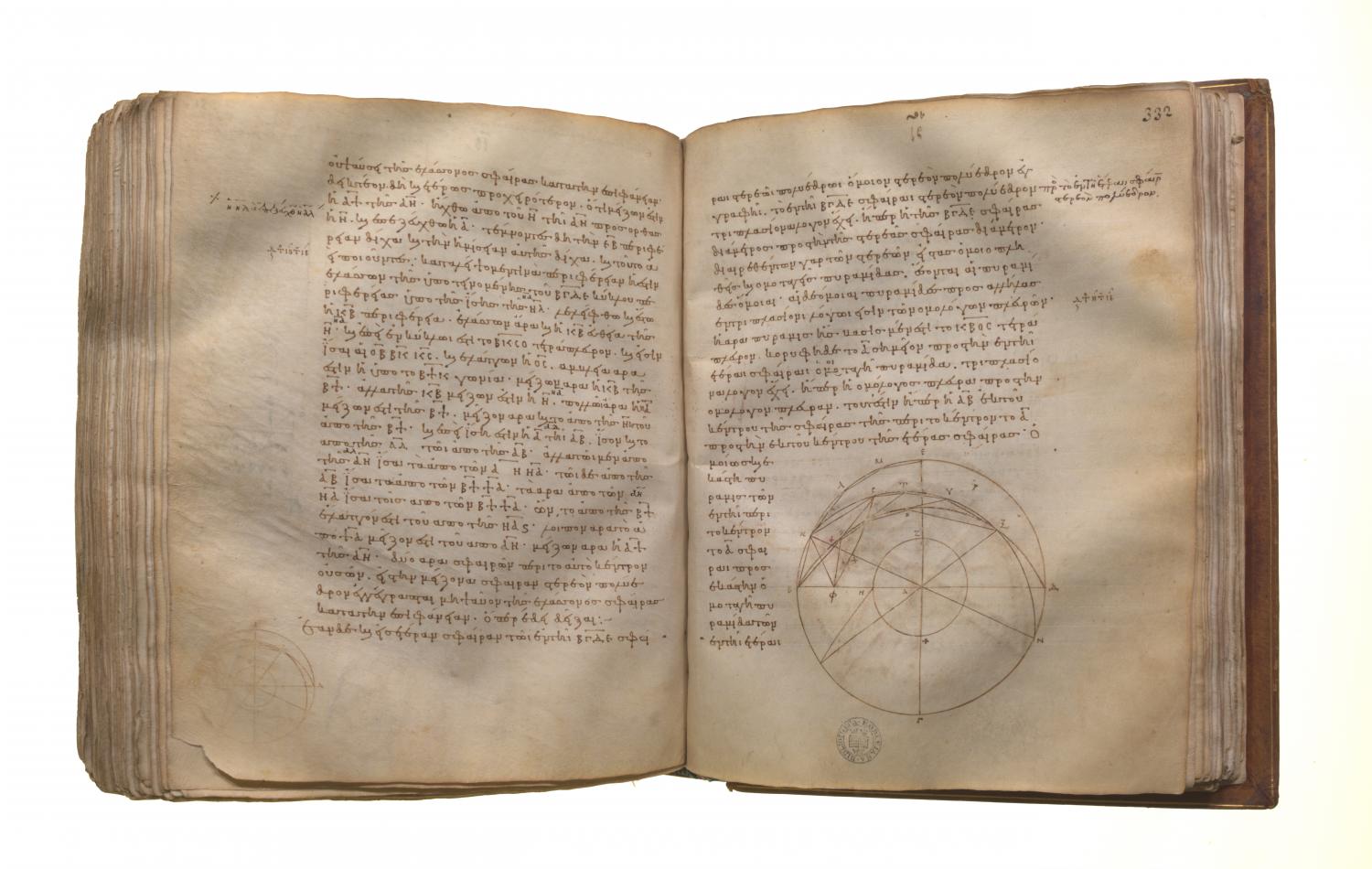

Given two spheres about the same centre, to inscribe in the greater sphere a polyhedral solid which does not touch the lesser sphere at its surface. Let two spheres be conceived about the same centre A; thus it is required to inscribe in the greater sphere a polyhedral solid which does not touch the lesser sphere at its surface. Let the spheres be cut by any plane through the centre; then the sections will be circles, inasmuch as the sphere was produced by the diameter remaining fixed and the semicircle being carried round it; [XI. Def. 14] hence, in whatever position we conceive the semicircle to be, the plane carried through it will produce a circle on the circumference of the sphere. And it is manifest that this circle is the greatest possible, inasmuch as the diameter of the sphere, which is of course the diameter both of the semicircle and of the circle, is greater than all the straight lines drawn across in the circle or the sphere. Let then BCDE be the circle in the greater sphere, and FGH the circle in the lesser sphere; let two diameters in them, BD, CE, be drawn at right angles to one another; then, given the two circles BCDE, FGH about the same centre, let there be inscribed in the greater circle BCDE an equilateral polygon with an even number of sides which does not touch the lesser circle FGH, let BK, KL, LM ME be its sides in the quadrant BE. let KA be joined and carried through to N, let AO be set up from the point A at right angles to the plane of the circle BCDE, and let it meet the surface of the sphere at O, and through AO and each of the straight lines BD, KN let planes be carried; they will then make greatest circles on the surface of the sphere, for the reason stated. Let them make such, and in them let BOD, KON be the semicircles on BD, KN. Now, since OA is at right angles to the plane of the circle BCDE, therefore all the planes through OA are also at right angles to the plane of the circle BCDE; [XI. 18] hence the semicircles BOD, KON are also at right angles to the plane of the circle BCDE. And, since the semicircles BED, BOD, KON are equal, for they are on the equal diameters BD, KN, therefore the quadrants BE, BO, KO are also equal to one another. Therefore there are as many straight lines in the quadrants BO, KO equal to the straight lines BK, KL, LM, ME as there are sides of the polygon in the quadrant BE. Let them be inscribed, and let them be BP, PQ, QR, RO and KS, ST, TU, UO, let SP, TQ, UR be joined, and from P, S let perpendiculars be drawn to the plane of the circle BCDE; [XI. 11] these will fall on BD, KN, the common sections of the planes, inasmuch as the planes of BOD, KON are also at right angles to the plane of the circle BCDE. [cf. XI. Def. 4] Let them so fall, and let them be PV, SW, and let WV be joined. Now since, in the equal semicircles BOD, KON, equal straight lines BP, KS have been cut off, and the perpendiculars PV, SW have been drawn, therefore PV is equal to SW, and BV to KW. [III. 27, I. 26] But the whole BA is also equal to the whole KA; therefore the remainder VA is also equal to the remainder WA; therefore, as BV is to VA, so is KW to WA; therefore WV is parallel to KB. [VI. 2] And, since each of the straight lines PV, SW is at right angles to the plane of the circle BCDE, therefore PV is parallel to SW. [XI. 6] But it was also proved equal to it; therefore WV, SP are also equal and parallel. [I. 33] And, since WV is parallel to SP, while WV is parallel to KB, therefore SP is also parallel to KB. [XI. 9] And BP, KS join their extremities; therefore the quadrilateral KBPS is in one plane, inasmuch as, if two straight lines be parallel, and points be taken at random on each of them, the straight line joining the points is in the same plane with the parallels. [XI. 7] For the same reason each of the quadrilaterals SPQT, TQRU is also in one plane. But the triangle URO is also in one plane. [XI. 2] If then we conceive straight lines joined from the points P, S, Q, T, R, U to A, there will be constructed a certain polyhedral solid figure between the circumferences BO, KO, consisting of pyramids of which the quadrilaterals KBPS, SPQT, TQRU and the triangle URO are the bases and the point A the vertex. And, if we make the same construction in the case of each of the sides KL, LM, ME as in the case of BK, and further in the case of the remaining three quadrants, there will be constructed a certain polyhedral figure inscribed in the sphere and contained by pyramids, of which the said quadrilaterals and the triangle URO, and the others corresponding to them, are the bases and the point A the vertex. I say that the said polyhedron will not touch the lesser sphere at the surface on which the circle FGH is. Let AX be drawn from the point A perpendicular to the plane of the quadrilateral KBPS, and let it meet the plane at the point X; [XI. 11] let XB, XK be joined. Then, since AX is at right angles to the plane of the quadrilateral KBPS, therefore it is also at right angles to all the straight lines which meet it and are in the plane of the quadrilateral. [XI. Def. 3] Therefore AX is at right angles to each of the straight lines BX, XK. And, since AB is equal to AK, the square on AB is also equal to the square on AK. And the squares on AX, XB are equal to the square on AB, for the angle at X is right; [I. 47] and the squares on AX, XK are equal to the square on AK. [id.] Therefore the squares on AX, XB are equal to the squares on AX, XK. Let the square on AX be subtracted from each; therefore the remainder, the square on BX, is equal to the remainder, the square on XK; therefore BX is equal to XK. Similarly we can prove that the straight lines joined from X to P, S are equal to each of the straight lines BX, XK. Therefore the circle described with centre X and distance one of the straight lines XB, XK will pass through P, S also, and KBPS will be a quadrilateral in a circle. Now, since KB is greater than WV, while WV is equal to SP, therefore KB is greater than SP. But KB is equal to each of the straight lines KS, BP; therefore each of the straight lines KS, BP is greater than SP. And, since KBPS is a quadrilateral in a circle, and KB, BP, KS are equal, and PS less, and BX is the radius of the circle, therefore the square on KB is greater than double of the square on BX. Let KZ be drawn from K perpendicular to BV. Then, since BD is less than double of DZ, and, as BD is to DZ, so is the rectangle DB, BZ to the rectangle DZ, ZB, if a square be described upon BZ and the parallelogram on ZD be completed, then the rectangle DB, BZ is also less than double of the rectangle DZ, ZB. And, if KD be joined, the rectangle DB, BZ is equal to the square on BK, and the rectangle DZ, ZB equal to the square on KZ; [III. 31, VI. 8 and Por.] therefore the square on KB is less than double of the square on KZ. But the square on KB is greater than double of the square on BX; therefore the square on KZ is greater than the square on BX. And, since BA is equal to KA, the square on BA is equal to the square on AK. And the squares on BX, XA are equal to the square on BA, and the squares on KZ, ZA equal to the square on KA; [I. 47] therefore the squares on BX, XA are equal to the squares on KZ, ZA, and of these the square on KZ is greater than the square on BX; therefore the remainder, the square on ZA, is less than the square on XA. Therefore AX is greater than AZ; therefore AX is much greater than AG. And AX is the perpendicular on one base of the polyhedron, and AG on the surface of the lesser sphere; hence the polyhedron will not touch the lesser sphere on its surface. Therefore, given two spheres about the same centre, a polyhedral solid has been inscribed in the greater sphere which does not touch the lesser sphere at its surface. Q. E. F.Porism. But if in another sphere also a polyhedral solid be inscribed similar to the solid in the sphere BCDE, the polyhedral solid in the sphere BCDE has to the polyhedral solid in the other sphere the ratio triplicate of that which the diameter of the sphere BCDE has to the diameter of the other sphere. For, the solids being divided into their pyramids similar in multitude and arrangement, the pyramids will be similar. But similar pyramids are to one another in the triplicate ratio of their corresponding sides; [XII. 8, Por.] therefore the pyramid of which the quadrilateral KBPS is the base, and the point A the vertex, has to the similarly arranged pyramid in the other sphere the ratio triplicate of that which the corresponding side has to the corresponding side, that is, of that which the radius AB of the sphere about A as centre has to the radius of the other sphere. Similarly also each pyramid of those in the sphere about A as centre has to each similarly arranged pyramid of those in the other sphere the ratio triplicate of that which AB has to the radius of the other sphere.