Translations

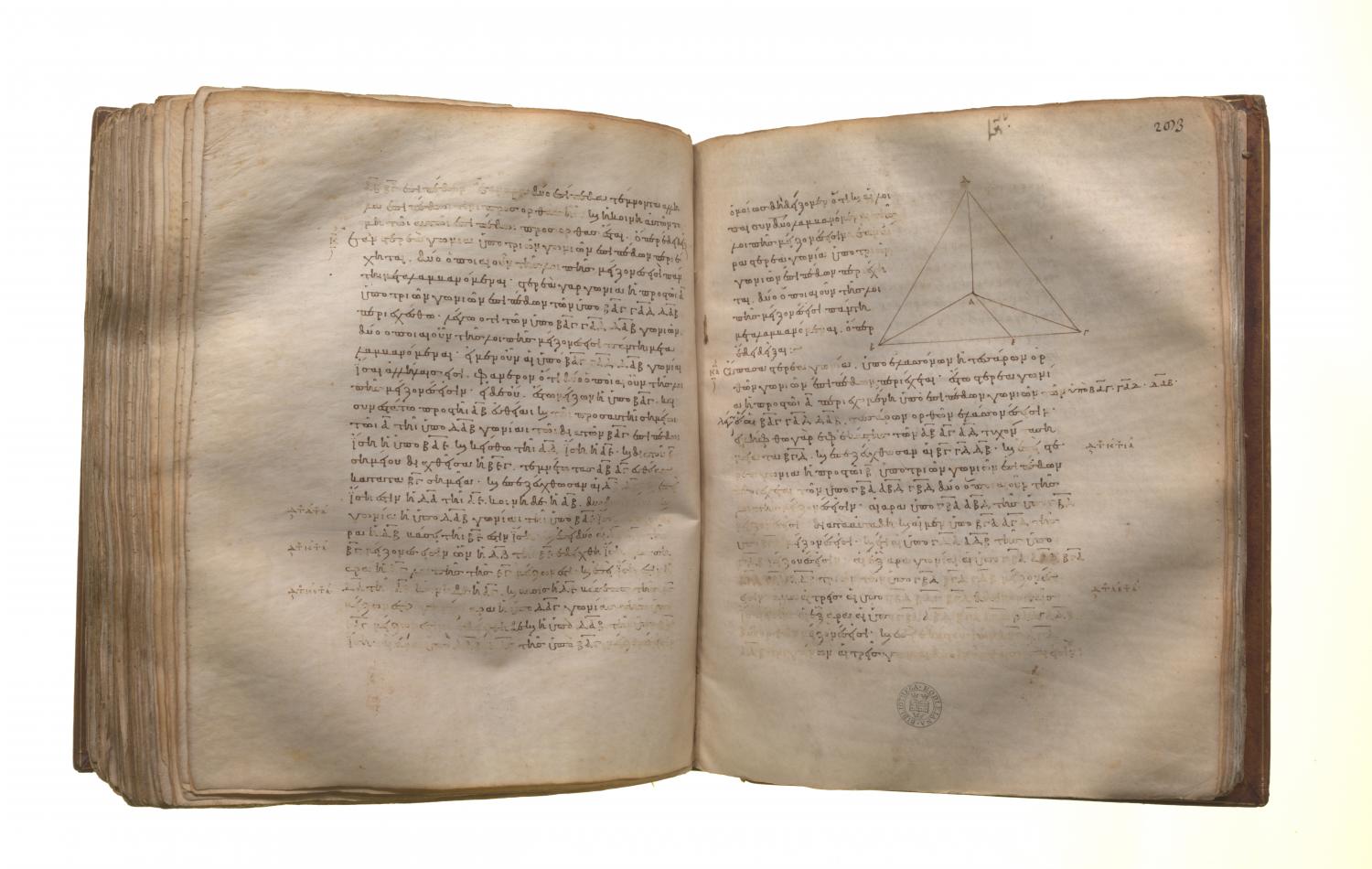

If a solid angle be contained by three plane angles, any two, taken together in any manner, are greater than the remaining one. For let the solid angle at A be contained by the three plane angles BAC, CAD, DAB; I say that any two of the angles BAC, CAD, DAB, taken together in any manner, are greater than the remaining one. If now the angles BAC, CAD, DAB are equal to one another, it is manifest that any two are greater than the remaining one. But, if not, let BAC be greater, and on the straight line AB, and at the point A on it, let the angle BAE be constructed, in the plane through BA, AC, equal to the angle DAB; let AE be made equal to AD, and let BEC, drawn across through the point E, cut the straight lines AB, AC at the points B, C; let DB, DC be joined. Now, since DA is equal to AE, and AB is common, two sides are equal to two sides; and the angle DAB is equal to the angle BAE; therefore the base DB is equal to the base BE. [I. 4] And, since the two sides BD, DC are greater than BC, [I. 20] and of these DB was proved equal to BE, therefore the remainder DC is greater than the remainder EC. Now, since DA is equal to AE, and AC is common, and the base DC is greater than the base EC, therefore the angle DAC is greater than the angle EAC. [I. 25] But the angle DAB was also proved equal to the angle BAE; therefore the angles DAB, DAC are greater than the angle BAC. Similarly we can prove that the remaining angles also, taken together two and two, are greater than the remaining one.